How Europe's main gay pride march was held in Belgrade

"Would you like a free raincoat? We can also offer you an HIV and syphilis test for free," a girl greeted you at the entrance to Belgrade's Tasmajdan Stadium.

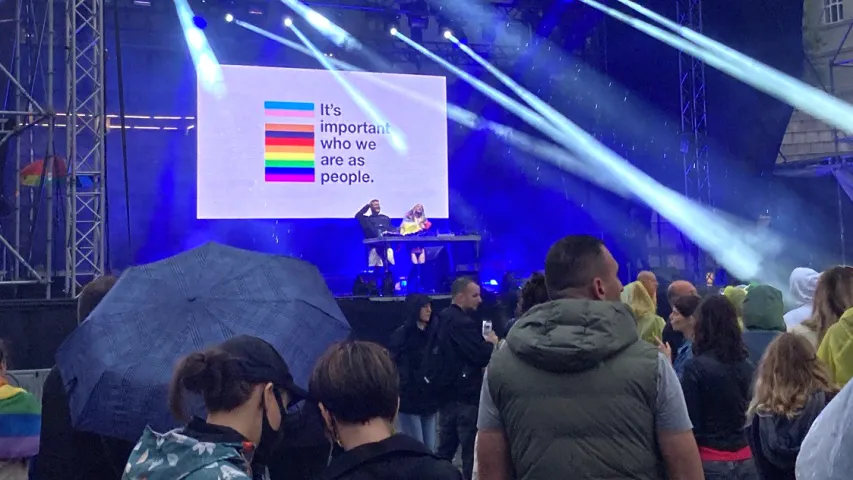

Saturday night, less than a day before Europride, is an event that attracts guests from Europe and the U.S., China, Australia and other countries. A sort of pre-party is taking place. It is a concert at the stadium the day before the event. It rains all day in Belgrade, so there aren't many people, but there are those who are ready to dance in the rain well past midnight.

Spectators walk through Tasmajdan Park past the monument to Heydar Aliyev, the father of the current president of Azerbaijan. He could hardly have imagined that he would accompany LGBT youths to an event with free condoms and drag shows.

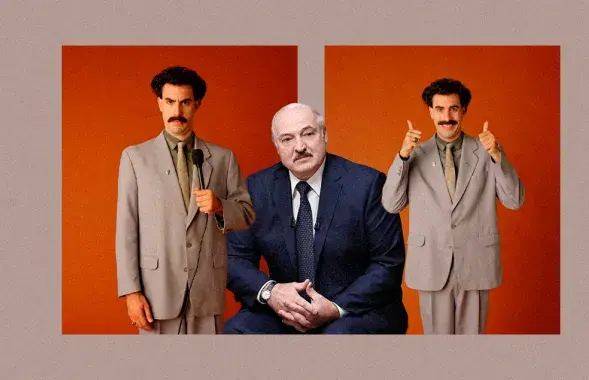

To get to the stadium from either side, you need to get past the police cordons: there are almost as many of them as there were on August 9-11, 2020, in the center of Minsk. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic banned the Pride march, but the police came anyway: not to prevent the gathering at the pre-party, but to protect the audience from extreme right-wing and religious activists who had promised to prevent the main event from taking place. But the right-wingers weren't here this evening as they were preparing their forces for the main day.

"This is a performance for Europe"

The organizers had given the Pride parade participants an hour and a half to assemble: everyone was supposed to come to one of the main streets, to the Constitutional Court, to protest the Serbian authorities' LGBT policies and then march to the same Tasmajdan stadium. Initially, the plan was different, but after Vucic's decision, it had to be adjusted.

On Saturday, the plan had to be changed again: just an hour before the event, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić announced that the march would take place and that she would guarantee its security.

It is impossible to get to the Constitutional Court: all aisles are blocked by cordons.

"Does anyone speak English?" we asked a group of policemen.

They look at each other, then one of them says "No" and points to the side: "Move away!" Everything happens at the crossroads: there are cordons on both sides, and more than a thousand people are "trapped" between them. You can neither move apart nor go to the place of the Pride. European diplomats who had decided to support the participants in the event are in the same situation.

"We don't know what to do next," says a member of the diplomatic corps. She's holding a small rainbow flag with the stars of the European Union. "We wait, nothing is clear yet".

The cops are blocking the road for a reason: right behind them is a group of right-wing and religious activists, including football fans. They shout curses at the Pride participants, sometimes start chanting "Family, family!" and sometimes try to break through the cordon.

Not only members of the LGBT community, but also the so-called allies are among the participants of the Pride march. Mira, for example, was a TV technician at a local television station before she retired, and now she supports the country's pro-choice movements.

"All that's going on, is a performance for Europe and for progressive Serbs. They try to show that they are protecting us, but in fact they do not allow us to hold a normal Pride march. It happens not only with Pride, it happens with all our actions. It's Vucic's nationalists, he sends them out and then as if he is holding them back," Mira says and nods toward the police and right-wing activists.

"Why does he need this?"

"He tries to sit on many chairs at once," smiles Mira. "He wants to show something to Brussels, to the local nationalists and to Moscow.But in some spheres the situation is even worse than in Yugoslavia. The country is going the wrong way".

The police do not allow the Pride participants to approach their cordon, but a young guy tries to approach and raises his placard in Serbian so that it can be seen by the opponents of the Pride. He admits that he does not speak English well, but explains the essence of the poster: "First they want to ban LGBT, then there will be women's rights and so on".

A similar thesis is supported by many. One poster reads, "If there is no equality for everyone, there is none for anyone."

"Better than in Russia and Belarus"

In this position, locked on both sides by police cordons, people spend an hour. Standing outside one of the stores closed because of the event are Amir, Lyosha and Sonya -- they are from Russia, and they moved to Serbia shortly after the war began.

"The Pride is about showing up so that society knows we exist," Sonya says. "After all, if someone is not seen, the psyche is constructed in such a way that they perceive him as hostile. This can be corrected".

"You see, here, the police at least protect us from soccer fans," adds Amir. "And what would it be like at home? It's scary to imagine, really. We've been here for more than half a year, but we got a little tense when so many cops showed up. But I do not think anything will happen, even though it is Serbia, it is better here than in Russia or Belarus. A Serbian friend told me that about ten years ago, they used to throw Molotov cocktails at the Pride. Today, it's not like that anymore -- progress".

After an hour, the police regroup: they create a corridor along which one can walk to the street where the parade is scheduled to begin. There are guards along the entire route. After five hundred meters, a group of religious fans can be seen on the left: they sing and hold up high placards with slogans against the Pride, but they cannot approach. A woman is standing right in the path, pointing a cross at the event participants with one hand, videotaping it with the other, and reciting prayers. Passers-by send her air kisses.

On the left, where a couple of hundred religious fans have gathered, chants can be heard, and on the right, songs by Rihanna and Beyoncé. A small platform is already there with several thousand people. Rainbow flags, posters, and original costumes (one of the participants came from Italy and dressed up like Jesus: a crown of thorns and an LGBT flag instead of a toga). Some came with flags of their countries: Germany, Israel, and Lebanon. Nearby is the Czech embassy building, where a group of diplomats is standing on the balcony, waving to the crowd.

"This is the mascot of the Belgrade Pride; his name is Luck," says a woman standing at the beginning of the column and showing the doll. "He'll bring us luck, too."

Police officers and men in security T-shirts guard the group from all sides. ABBA is played loudly, and a group of diplomats take pictures with the European Commissioner for Equality who has arrived at the Pride march. A group of young people is exchanging contacts. And on the left, on the wall of one of the houses, the letter Z is painted, and there is also an inscription about May 9. Someone later tried to cover the letter with a Ukrainian flag.

The column's path to the park passes through St. Mark's Church. It is completely cordoned off, with a group of protesters standing on the steps and raising crosses high. As the column approaches the church, bells ring until the latter has moved far enough away. Opponents of the Pride are not just here: there are violent clashes in other parts of the city, also blocked off by police. More than 60 people have been detained. But Pride participants don't find out about this until later, from the news.

After passing the monument to Heydar Aliyev again, everyone approaches the stadium. At the entrance, several men hand out paper bracelets.

"It's a stupid rule, but you can't do without it. I didn't invent this rule; I don't need it at all: I might be naked on stage in an hour, but this idiocy is here," complains one of them.

Some people go straight to the outlets, where they can get a soda or a beer. Others take seats under the stage, where the performances had already begun. This is how Europe's main LGBT Pride march ended: with a concert party until late at night.

Police officers still block off parts of Belgrade - they don't move from their seats until late at night. Serious incidents are avoided.