Strings, Oil, and BelAZ: How Belarusians Turn a Profit in the Russian Arctic

BELAZ Technical Support Center in Murmansk Region / t.me/minskiygorispolkom

Belarus doesn’t have any territory in the Arctic. However, this hasn't prevented it from actively participating in infrastructure projects within the Arctic Circle—and even fantasizing grand schemes about its prospects there.

This heated activity is supposedly driven by economic interest. In northern Russia, there are ports—something Belarusian exporters sorely need due to sanctions—as well as resources, ranging from oil to fish. And indeed, the Arctic market can make for a promising sales outlet for BelAZ trucks. Or so it seems.

Arctida and Euroradio reveal who exactly from Belarus is permitted by Russia to work in the Arctic, the nature of the money involved, and altogether, whether these projects prioritize profit or politics.5

Go [North-]East

In the fall of 2020, reports emerged that Belarus had used the Northern Sea Route for the first time to deliver potash fertilizers to China. Thereafter, Lukashenko attempted to blackmail Lithuania with the threat of redirecting transport flows entirely. He wagered that without Belarusian potash, the port in Klaipeda would quickly face economic ruin.

But soon enough, the threats backfired: Belarus lost access to the Baltic Sea due to international sanctions. As a result, Russian ports, including Arctic ones, transitioned from being an instrument of leverage to an unavoidable dependency.

“Redirecting Belarusian exports from Lithuanian and Latvian ports to Russian ones was a painful and unavoidable measure. Logistics costs increased by 10–50%, depending on the conditions and tariffs,” an expert from the Center for New Ideas told Euroradio. “Russian seaports are overloaded, which also affects the cost and time needed to handle export flows passing through them.”

“In the end, given that a significant share of Belarusian exports consists of oil products, the situation appears quite absurd. Belarus first purchases crude oil from Russia, refines it domestically, and then has to pay again for exporting those products through Russian territory.”

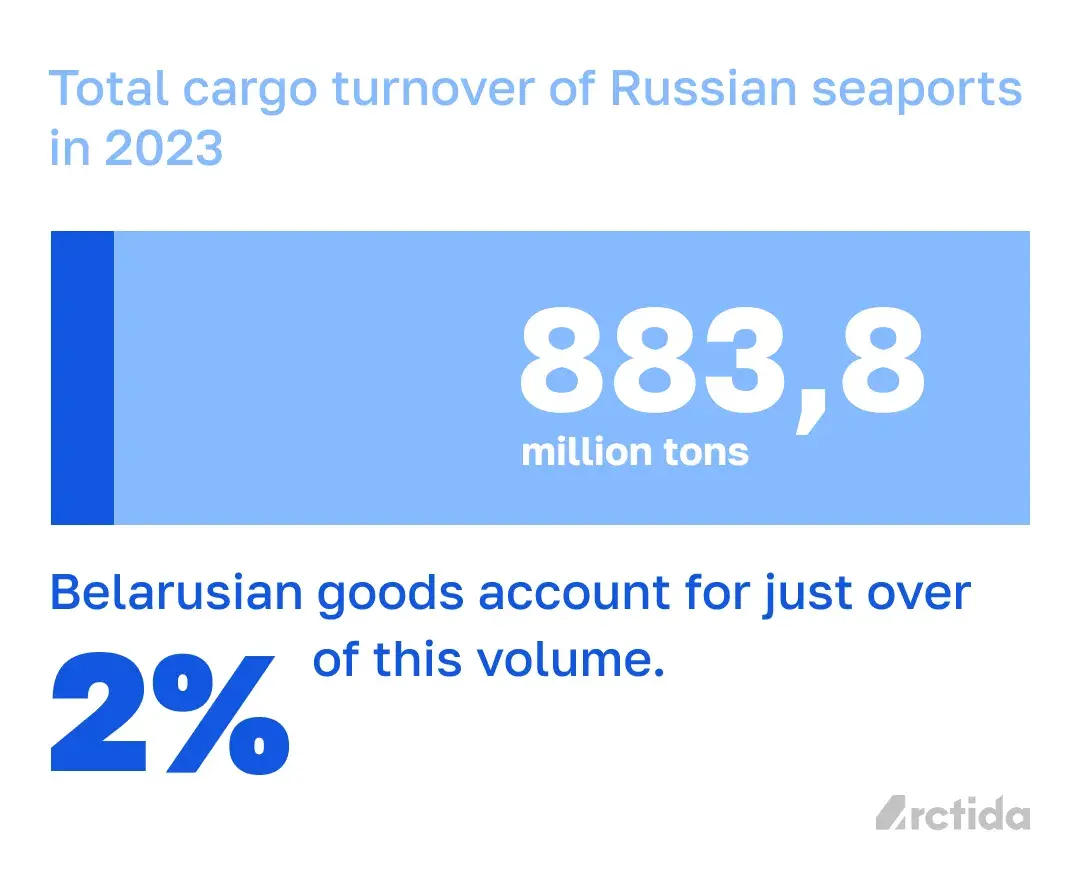

In 2023, Russian ports handled 14.1 million tons of Belarusian goods. Dmitry Krutoy, then the Belarusian ambassador to Russia, cited data on cargo transshipment to compare this volume to the record-breaking amount processed through the Baltic states and Ukrainian ports in 2019, then amounting to 18.8 million tons. In 2023, the total cargo turnover at Russian seaports reached 883.8 million tons, making Belarusian goods account for just over 2% of this total.

In April 2024, construction began on a multimodal cargo terminal in the Murmansk region to support Belarusian trade interests. This terminal will be part of the developing Lavna port, and is expected to handle its first shipments by 2028. Investments are estimated at 20 billion Russian rubles ($205 million).

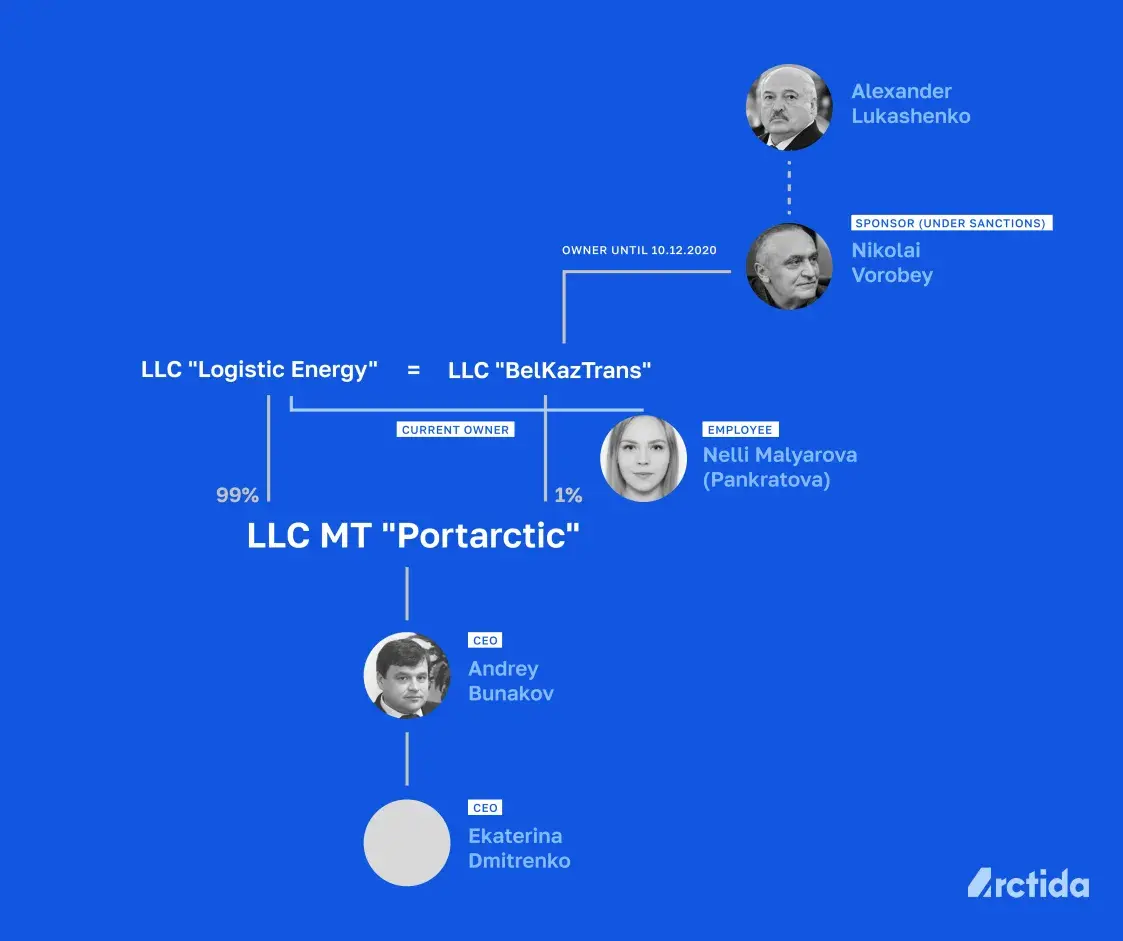

Its funding comes from private businesses closely linked to "Lukashenko's wallet," Nikolai Vorobei. The terminal is owned by Port Arctic LLC (formerly Arctic Gate LLC, renamed in September 2024 for a more English-sounding rebranding). Its director until recently was Andrey Bunakov, former head of Belshina, who is under U.S. sanctions and was previously arrested in Belarus on fraud charges.

According to the service Kontur.Fokus, as of November 2, the new general director is Ekaterina Sergeyevna Dmitrenko. Little is known about her. Leaked data suggests that, under her name, terminal construction was managed for Gazprom Neft and St. Petersburg Oil Terminal LLC. This information is corroborated by her LinkedIn profile.

99% of the legal entity Port Arctic LLC is owned by Belarusian company Logistic Energy LLC, which is in turn owned by Belarusian citizen Nelli Malyarova (Pankratova). The remaining 1% is directly held by Malyarova.

Journalists describe Logistic Energy LLC as a rebranding of BelKazTrans, a company owned by oligarch Nikolai Vorobyov. Malyarova is its nominal asset holder.

"In the summer of 2024, agreements were signed to begin construction of a Belarusian port terminal in Murmansk. It is slated to be used for exporting potash fertilizers via the Northern Sea Route. But how long it would actually take to complete this port, and how much it could ultimately cost Belarus, remain open questions," continues the expert from the Center for New Ideas.

Moreover, officials in Arkhangelsk proposed that Lukashenko "consider" building a terminal there as well. However, discussions have yet to progress beyond initial negotiations and cost estimates.

The Arctic is the New Venezuela

Since 2011, Belorusneft-Sibir has been operating in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Region, providing drilling equipment maintenance, geological exploration, and logistics services. Among its major clients are Rosneft, Gazpromneft, Novatek, and the Belarusian joint-stock company NK Yangpur, for which Belorusneft-Sibir has drilled more than 90% of the wells over the past decade.

NK Yangpur is the first Belarusian oil-producing asset in the Russian Arctic. Belorusneft acquired it in 2013. As of the end of 2023, NK Yangpur held four license areas and was developing 12 fields. According to Belorusneft General Director Alexander Lyakhov, the company produced over 350,000 tons of oil and gas condensate in 2023 and was "close to reaching a total of 1 billion cubic meters of associated and natural gas."

Lyakhov estimates that expanding drilling to new licensed areas could elevate NK Yangpur's production to levels comparable to Belarus's domestic output (in 2023, republican unitary enterprise PO Belorusneft achieved an oil production level of 1.87 million tons). In January 2024, the company announced plans to build a gas processing plant in the Russian Arctic. However, to date there is no information on the start of construction or related activities.

“The profit from Belorusneft's Arctic subsidiaries is not that substantial—about $80 million last year. Even if oil production increases to 2 million tons, the financial impact is unlikely to change significantly.”

“Ultimately, Belarus’s footprint in Russia's oil market is small. Interestingly, during the peak of Belarus-Venezuela relations (in the late 2000s and early 2010s), Belorusneft was able to quickly establish operations in Venezuela comparable in scale to its Russian projects. This highlights how modest and slow the company's growth has been in the Russian market,” describes the expert from the Center for New Ideas.

Bikers Turn a Profit from BelAZ Operations

Machinery produced in Belarus is actively used by companies engaged in Arctic mineral extraction—аbove all, BelAZ mining dump trucks. In 2023, the Zhodino-based factory signed an agreement with the government of the Murmansk region to open a service center to service machinery in the city of Apatity.

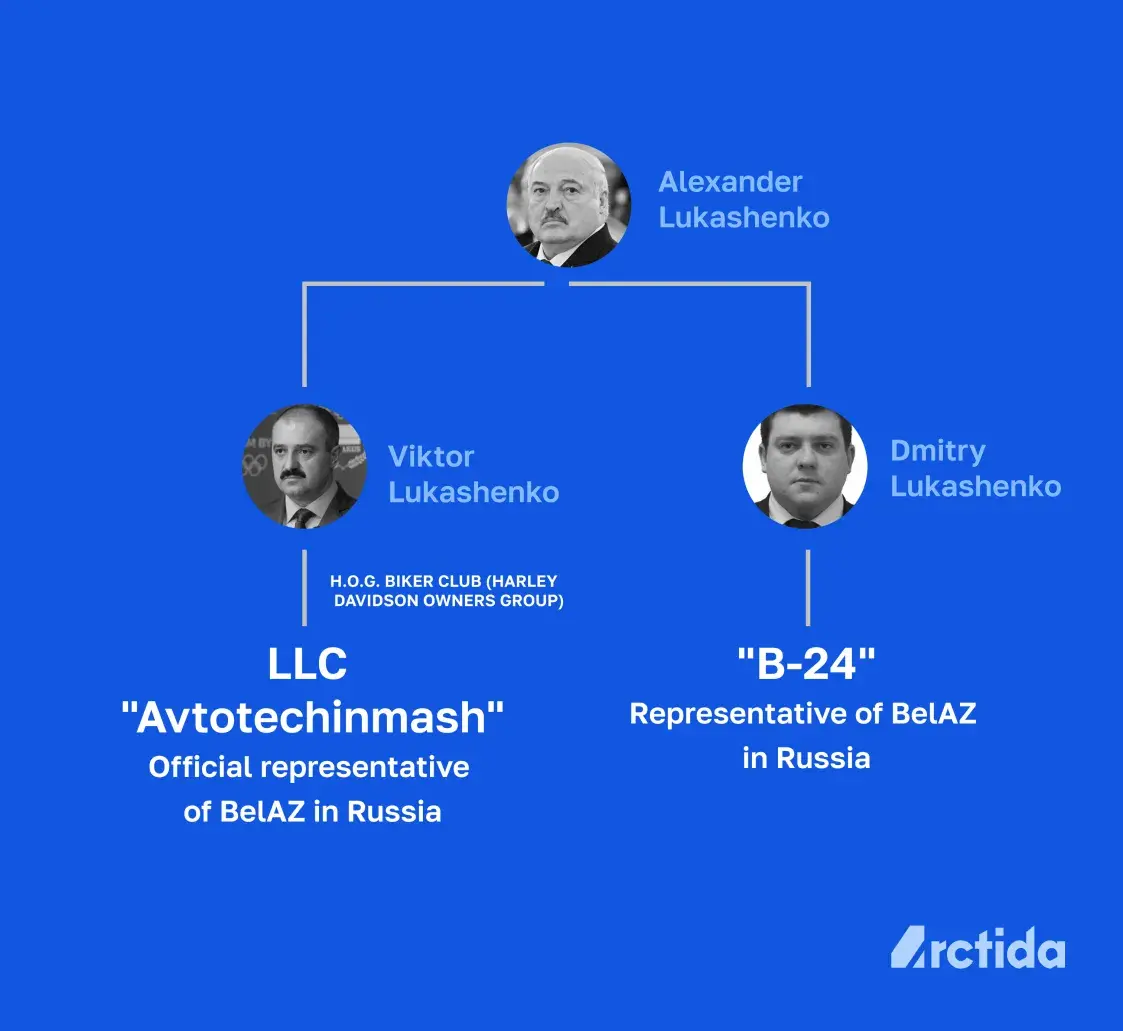

As part of the same agreement, an educational center was established in 2023 at a branch of the Murmansk Arctic State University. This center trains specialists who plan to work with BelAZ machinery. It was opened in collaboration with Avtotehinmash LLC, an official BelAZ representative in Russia registered in Smolensk. Avtotehinmash has ties to friends of Viktor Lukashenko through the Belarusian branch of the Harley-Davidson Owners Group (H.O.G.), Minsk Chapter.

In Karelia, since 2018, Amkodor-Onego — a branch of the open joint-stock company Amkodor—has been operating to produce forestry equipment. The company is owned by Belarusian businessman Alexander Shakutin, whom investigative journalists describe as yet another financial proxy for Lukashenko. Shakutin is under EU sanctions.

A "Russian Sea" for the Belarusian "Santa"

A Belarusian-Russian joint venture, SP Soyuzryba LLC, is registered in Murmansk and engages in fishing within Russia's exclusive economic zone in the Baltic and Barents Seas.

In 2023, the company's quota amounted to approximately 5,500 tons, a decrease from 2021, when the quota was around 7,800 tons. The enterprise supplies raw materials to food producers Russkoye More (Russian Sea) and Santa Bremor LLC.

The owner of Santa Bremor, Alexander Moshensky, was a trusted confidant of Lukashenko in 2010, received an order of merit from him in 2013, and in 2019, through a personal directive from Lukashenko, acquired two state-owned factories directly without an auction. In 2013, 2016, and 2019, Moshensky accompanied Lukashenko and his family on private jet trips as part of his inner circle.

In 2021, Moshensky relocated to Warsaw. He argued that this was necessary for commuting westward to meetings, which was otherwise impossible from Minsk due to sanctions imposed on Belarusian aviation. As of late October 2024, Moshensky is not under personal sanctions.

Strange Technologies

In September 2024, the Russian popular science website Naked Science published an article about a Belarusian project devised as an alternative to the Northern Sea Route. The plan envisions connecting Arctic ports and logistics hubs through a "high-speed land transport corridor."

Imagine a 10,600-kilometer-long tunnel supported by three-meter-high reinforced concrete pillars. Inside, high-speed pods soar through carrying passengers and freight, with a promised annual cargo capacity of up to 100 million tons. Sounds incredible, right? Perhaps, too incredible to believe. And skepticism, it seems, is warranted.

Behind the project is the "international engineering company" UST Inc., headquartered in Minsk. This initiative is linked to the so-called String Technologies developed by Anatoly Yunitskiy, a native of Belarus’s Gomel region, which caused a stir in Belarus about eight years ago.

At the time, Yunitskiy was actively raising investments from gullible patrons worldwide. He promised to create a rapid and eco-friendly "string transport" system using "innovative solutions," dismissively called Elon Musk a "boy from South Africa," and valued his intellectual property at $400 billion. Suffice it to say, no functioning example of string transport has been presented to date.

“The concept of string transport has been around for several decades. It involves the construction of vertical supports on which, to put it simply, steel beams housing pre-tensioned steel wires (or "strings") are placed. The idea is that passenger and freight transport could move along these beams like a railway, at speeds of no less than 150 km/h, ideally 500 km/h.

“The development of this technology has been extremely slow. Outside of Belarus, a small test track exists—rather, is still under construction—in the UAE alone. Recently, there has been some discussion about the potential use of string transport in Russia's Leningrad region, but only for passenger transit, not freight—for example, goods delivered to ports.”

“Even if there is some breakthrough, creating real infrastructure in the form of "string roads" that extend to Arctic ports would require significant time and resources—we're talking decades. And in the end, Yunitskiy has repeatedly faced accusations of fraud. Allegedly, his string transport enterprise is merely a way to attract funds for a knowingly unviable project”, explains our source from the Center for New Ideas.

An Empty Union

At the January 2024 convention of the Union State of Russia and Belarus, Lukashenko once again announced his interest in developing the Northern Sea Route for transporting Belarusian goods. Cooperation in the Arctic has been considered by the two countries as a potential area for the Union State’s development since 2015.

In 2018, the Arctic-SG foundation was established to organize "professional scientific-practical conferences and cultural-educational events" related to the Arctic. Its activities were intended to be funded through the state budgets and extra-budgetary funds from the two nations.

So, what has this foundation accomplished?

Over the past 2-3 years, the Arctic-SG foundation hasn’t conducted a single public activity. According to the Kontur.Focus service, it hasn’t submitted financial reports in the past year either, nor does it have any declared assets or recorded income during this period. Mandatory payments to the Pension Fund have been enforced through court rulings against Arctic-SG since 2019.

Belarus's presence in the Arctic is primarily tied to industries involved in industrial development there: namely, the extraction of natural resources such as oil and gas, as well as supporting sectors related to logistics and the use of the Northern Sea Route. The capital behind these ventures is typically linked to Lukashenko's family and associated oligarchs. Belarus's participation in Arctic projects takes place under the direct oversight of the Russian state.

Notwithstanding, Belarus's presence in the Arctic has different implications for Belarus and Russia, respectively. For Belarus, whether in terms of transport logistics or oil extraction, its contributions in the Arctic are modest compared to Russia's. Still, these operations remain significant in the absence of other viable options, particularly regarding the transportation of fertilizers.

For Russia, Belarus’s involvement is an example of another party contributing to the "common cause" of Arctic development—a demonstration of Russia’s willingness to cooperate. Yet, this collaboration is strictly controlled and operates in a non-transparent manner: while Russia allows Belarus to engage in Arctic ventures, it requires it to follow its lead in exploiting the region's resource base.

The exception is Yunitskiy's engineering "inventions," which, judging by their reality, seem more like a PR stunt. However, even this spectacle suits the current Russian context, which is no stranger to fantasizing.

Authors: Nail Farkhatdinov, Anastasia Martynova (Arktida analysts), Euroradio.