"Three Years in Solitary": Ukrainian Soldier Held Captive in East Ukraine

Иллюстрации: Тора

In the winter of 2015, Ukrainian soldier Yevhen Chudnetsov was captured in the occupied territories in the east of Ukraine. His fate became well-known after Russian media released a video of him. Russian-backed militants in the occupied territories wanted to sentence him to death, but outcry from international human rights activists led to him being given thirty years in a maximum security prison colony. This June, Yevhen turned 27. He has spent the last three years in prison. Hromadske tells the story of one of 132 Ukrainians who militants are holding captive.

“God, at least someone remembers us,” replies Nina Chudnetsova when we call to talk to her about her grandson. She is 75 years old. She doesn’t believe that she’ll get to see Yevhen free. He has spent the last two years in a single room in a Donetsk detention centre, and he was recently moved to a colony in Makiivka, another city in the Donetsk region in the east of Ukraine. According to the Interdepartmental Centre for the Exchange of Prisoners of the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU), Chudnetsov is one of 53 Ukrainians whose presence representatives of the occupied regions of Donetsk and Luhansk have confirmed. He is also one of the first on the list for exchange. But negotiations over exchanges have yet to lead to results. Chudnetsov’s grandmother, younger brother and sister are awaiting his return.

“Right Wing Donetsk”

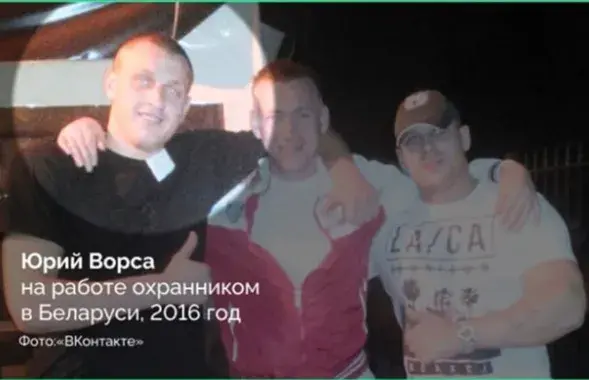

Yevhen Chudnetsov was born in Makiivka on June 29, 1990. Since childhood, he played a variety of sports: from mixed martial arts to sambo. He read a lot, was interested in politics and esoterics, Scandinavian mythology and runic writing. He has a tattoo – a black sun on his shoulder – done by his friend Anton Demidonok. They met as football fans.

Anton and Yevhen were part of a right-wing movement in Donetsk. “We all met at ‘Golovy’ [a meeting place near the Donetsk drama theatre]. Back then, it was possible, at any moment, to jump in the car and go straight from Makiivka to Donetsk without any problems. It was my hometown. We shared literature, music, ideas. We visited each other,” Anton tells Hromadske.

Anton says that in 2005, at the time of the Orange Revolution, Yevhen was affiliated with the founder of the organization “Donetsk Republic,” Andriy Purhyn: “Yevhen was associated with his organization ‘Eurasian Union of Youth.’ But these were just the guys that he went to school with or lived with in the same neighborhood. He was in it for company, so to speak.” In Anton’s words, when he and Yevhen met in 2007, Yevhen was already pro-Ukrainian.

From Makiivka to “Azov”

The Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) began for Chudentsov in 2014, when a shell landed in the stairwell of a neighbouring building in his complex. According to Anton, “he was sitting at his computer, reading, studying for exam. As far as I know he had a conflict with the ‘DPR’ militants. Old ‘friends’ warned him: ‘They’re already coming for you, and you have 20 minutes left.’ Yevhen gathered the necessities and went straight to the Azov Battalion at the invitation of a friend.” Those close to Yevhen suspect that the conflict could be linked to his patriotic posts online, which he published on his Vkontakte page not long before he escaped.

For a long time, Yevhen’s family didn’t know that he had left for the front. In the words of his friend Oleksiy Yukov, he deliberately did not tell them so as not to harm them. Yevhen was afraid that the family would react “extremely negatively” to his choice. Later, he told his mother that he was in the Azov Battalion.

Formed at the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in May 2014, the Azov Battalion was initially a volunteer militia. It was integrated into Ukraine’s National Guard in the autumn of that same year as a separate special purpose squad. Most of the Azov Battalion’s soldiers support Ukrainian nationalism are often associated with the far-right.

“His mother visited him regularly and he always sent her the majority of his salary. It was really admirable of him. She had almost nothing then. At that moment, Makiivka was very chaotic,” says Yevhen’s colleague, a soldier from the Azov Battalion named Artem Shevchenko, who asked to be identified by a fake name. He met Chudnetsov in September 2014 at one of the bases in Mariupol, a city in the south east of Ukraine near the Sea of Azov. They served together in the ATO.

“On the last day, we were heating up soup when strong shelling began. Then we parted. Everything was very chaotic – Azov soldiers were fighting with separatists. An enemy tank shot the armoured personnel carrier he was in. Yevhen and many others in his regiment received shrapnel wounds and concussions,” says Artem.

“Press Conference”

“I joined the Azov Battalion voluntarily in mid-October 2014,” says Chudnetsov from prison during the “press conference” arranged for the Russian media. He is covered in bruises and several of his front teeth are broken. “My friend invited me. I will not say what the circumstances were, but they were such that I had to leave Makiivka.” From this video recording and a later interview with state-owned Russian TV channel, Russia-1, Chudnetsov’s colleagues found out that he was alive. Now, the friend who called Yevhen to join the battalion has resigned from Azov. He refused to comment on Chudnetsov’s captivity.

The video Russian media published claimed that Chudnetsov voluntarily gave himself over to captivity: “In the last days, I often thought about why. Maybe because he didn’t want to fight any more,” says Yevhen’s grandmother. “I thought that I wouldn’t survive all of this.”

She also says that the Azov Battalion reassured her that Yevhen was forced to say that to save his life: In the words of Artem Shevchenko, Chudnetsov’s colleague, they let him live in order to create a stir around the fact that an Azov soldier had been detained.

Without a Mother

Chudnetsov did not receive immediate medical attention and his wounds developed pleurisy, inflammation in the membrane around his lungs. He ended up in the prison hospital. His friend, Anton Demidonok, says that later, Yevhen and the other captives cleared the fields and cleaned the bodies of those killed at the Donetsk airport:

“We called a woman from Mariupol whose father was in the same cell as Yevhen. While we were in contact with her, we sent messages through her, but now this possibility is no longer there. [Yevhen] has no support.”

When Yevhen was in prison after his “conviction,” his mother was diagnosed with a serious illness. She went several times to ask for a visit with her son but every time she was denied. She died a year and a half ago.

A Half-Hour Sentence

“Court sessions” concerning Yevhen Chudnetsov were held three times. Four criminal cases were brought against him and he was convicted under two articles of the “Criminal Code of the DPR”: undergoing training in an extremist organization and the overthrowing constitutional order. They also wanted to accuse Chudnetsov of torturing and abusing people, but found no witnesses or victims to confirm this.

“He didn’t have a lawyer and his relatives couldn’t come to the trial, nor could representatives from the international monitoring mission. This bears no resemblance to a proper judicial trial,” comments Tanya Lokshina, a researcher on Europe and Central Asia for Human Rights Watch.

Chudnetsov’s sister, Alana Chudnetsova, was only allowed to come to the third court hearing, but was told an incorrect time. The “verdict” was reached half an hour before her arrival.

“I saw Yevhen briefly after the sessions, and he burst into tears...He was handcuffed and he left,” his sister says.

“Alana – thirty!” Yevhen managed to shout, conveying his sentence, thirty years, to his sister as he was led out of the room.

Yevhen’s lawyer doesn’t answer calls. For a long time Yevhen’s relatives were denied meetings with him. Only in May of this year were they allowed visitation once a month.

50 Minutes of Freedom

“We talk through glass. They give us an hour. We talk about nothing: about family basically. They let him walk on the roof of the prison for 50 minutes a day. No one comes to him, he sits in the cellar, where they serve life sentences, and there’s no phone connection,” says Alana Chudnetsova.

Representatives from the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine told Hromadske that they can’t access Ukrainian prisoners in the occupied Donbas region.

Human rights activist Oleksandra Matviychuk says that Ukrainian human rights activists can’t get to Yevhen or any other hostages in the “DPR”: “The Red Cross was allowed to visit the detainees in the occupied regions of Donetsk and Luhansk last year. OSCE Representative Tony Frisch visited the detainees for the first time in October last year. For us, human rights activists, it’s simply impossible.”

During a visit to the self-proclaimed “DPR” last year, Ukrainian MP Nadiya Savchenko tried to visit Yevhen Chudentsov. “I asked if it was possible to see him. It was around the time when he was supposed to be convicted, and they didn’t give me access to him.”

Savchenko managed to visited already “convicted” prisoners. “Regarding the conditions of the guys that I saw –and this was mostly special forces from the third regiment –the prisons where they were located in didn’t different from those that exist in Ukraine. Very old buildings, mould, tuberculosis, cells –of course, everything bad.” However, according to Savchenko, the Ukrainian hostages in the “DPR” don’t have basic human rights and prisoners’ rights, they can’t receive messages or communicate with their relatives: “They are in solitary confinement, like I was in Russia.”

Future Exchange

Ex-Commander of the Azov Battalion Andriy Biletskiy says that the fact that he belonged to the regiment seriously complicates Chudnetsov’s release. “As far as we know he’s been transferred to the 32nd prison colony of Makiivka in the Donetsk region. He’s not being held with other prisoners of war. He’s considered a traitor and so on, because to them, he is a ‘citizen of the DPR’ and his situation is much worse, as is the situation of the other imprisoned Azov soldier, nicknamed ‘Sevastopol,’ who is now in Russia.”

The office of the Ukrainian Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights claims that the question of prisoner exchanges is seeing some motion for the first time in eight months.

“On Wednesday (June 21) at a Minsk meeting, a verification mechanism was adopted and I hope that this will unlock the exchange process,” says Mykhailo Chaplyha, representative of the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights.

Savchenko, on the other hand, expects that the next exchange could take place in July: “I hope that we can bring Yevhen back because he has already been convicted. And the policy in the occupied territories is the same as in Russia: Before conviction, they don’t return anyone.”

In total, there are 132 Ukrainian hostages on the list for exchange.

Background: The war in Ukraine started in 2014, when Russian forces invaded Donbas and annexed Crimea. Since then, more than 10,000 people have been killed and about 24,000 injured in Ukraine, according to UN reports. According to the European Commission, the conflict in eastern Ukraine has affected over 4.4 million people, 3.8 million of whom are believed to be in need of humanitarian aid.

en.hromadske.ua // By Darka Hirna

/Translated by Eilish Hart, Matthew Kupfer

/Illustrations: Tora