West bought political prisoners from GDR regime. Can Belarusians do the same?

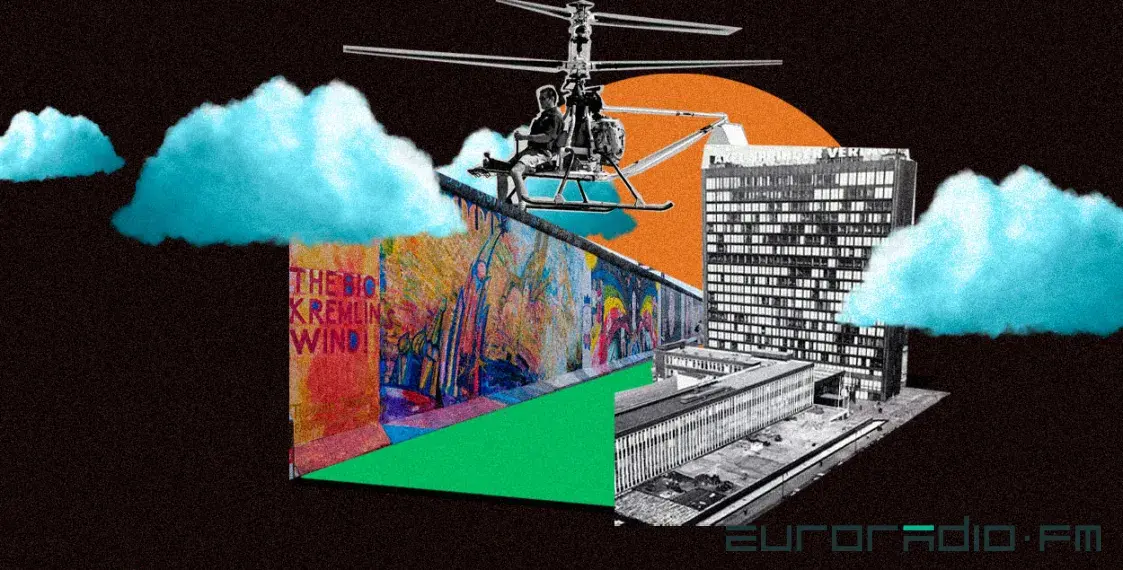

The Berlin Wall / калаж Улада Рубанава, Еўрарадыё

Michael Schlosser worked for East German television and dreamed of opening his own garage. Schlosser was an excellent mechanic. Spoiler: To escape the GDR, he would build... an airplane!

But in the early '80s, East Germany didn't know its citizen was capable of such a thing. So they refuse to let Schlosser open a workshop. He writes again and is rejected again.

"And then I thought: if they don't want me as a good mechanic in my country, I'll have to go to the West. But at that time I didn't understand how to do it," Michael Schlosser told Euroradio.

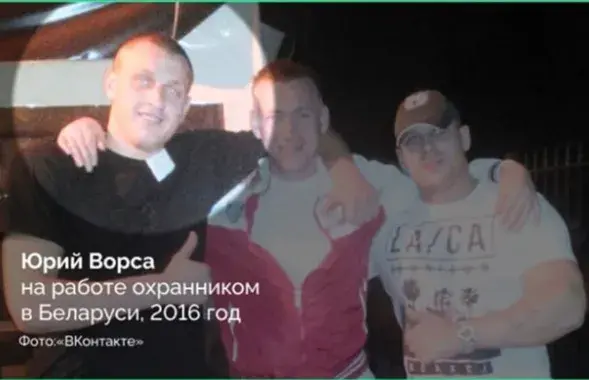

We meet him in the education and memorial building of the Kasberg prison in the East German city of Chemnitz. When Mr. Schlosser came here in the '80s, the city was called Karl-Marx-Stadt, and this building was not a memorial, just a prison. Political prisoners from the GDR were waiting for West Germany to buy them back from the Eastern regime.

That's right, buy them out. In total, the German government bought more than 33,000 political prisoners from the GDR regime. Michael Schlosser was one of them.

In the special project "The Birdcage", Euroradio tells this fantastic story.

"So I decided to build a small, single-engine plane"

Schlosser hatched plans to escape the GDR. But the final plan took shape of its own accord when he visited Czech friends and turned on the radio.

"I was sitting at the campsite, listening to the radio, when I heard an announcement from the Axel Springer publishing house: they said that Axel Springer was offering their roof as a landing place for GDR citizens who wanted to leave the country and could build a helicopter," says Michael Schlosser. "The statement said that the GDR resident who could fly to West Berlin in a homemade helicopter would receive a bonus of one million West German marks".

Axel Springer is one of Europe's largest publishing and media companies. In 1966, the company built a high-rise building for its headquarters right next to the Berlin Wall. That's where the helicopter was supposed to land.

"At first I didn't take this suggestion seriously. But a friend of mine from the Czech Republic contacted Axel Springer. The editor came to the phone and confirmed: yes, we made such an announcement. I couldn't build a helicopter because I didn't have enough blueprints, so I decided to build a small single-engine plane".

The escape was scheduled for November 11, 1983. Schlosser planned to fly between five and six in the morning. That was the start of Carnival in Germany, and he thought everyone would be drinking at the border and his plane wouldn't be noticed.

"What I didn't know was that the Stasi already had a warrant to search my property".

The Stasi had been watching Schlosser. Someone at work said that this mechanic was spending too much time studying a Hungarian magazine and reading too closely an article about hang gliders. When Michael went to the newsstand to get the latest issue of the magazine, he was asked for his passport information. The magazine is out of print, but we will order it for you. Even then, Schlosser began to suspect that he had attracted the attention of the Ministry of State Security. Why else would he ask for passport information for a magazine?

"When it became possible to read my documents, the investigation reports, I learned that they consisted of more than 5,000 pages".

We ask, "Thousands?" And Michael Schlosser spreads his hands to show the impressive volume of the imaginary file. Yes, five thousand pages. The Stasi knew all about his plans.

Schlosser was sentenced to four years and four months in prison for attempting to flee East Germany. The plane that was ready to take off was taken away. Schlosser still doesn't know where it is (he has since built three more).

"But I only spent six and a half months in prison. On my papers it says: this man wants to be ransomed, permission has been given to ransom him," says Michael Schlosser. "In October 1984, I arrived at the prison in Karl-Marx-Stadt. And on December 5, 1984, West Germany ransomed me from the GDR".

We are talking in the very prison where Schlosser was waiting to be released. About 90% of all political prisoners for whom the West intervened were transferred here on the eve of the ransom.

How did the ransom negotiations become possible?

In 1962, Soviet spy Rudolf Abel was exchanged for American pilot Henry Powers, signaling that negotiations between the warring regimes were possible. You may have seen the story of this exchange through the eyes of Steven Spielberg, who chronicled the complex negotiations behind the deal in the Academy Award-winning film Bridge of Spies.

And shortly after Abel was swapped for Powers, in 1963, the federal government exchanged 8 prisoners for more than 200,000 German marks, according to Dr. Stefi Lehmann, a researcher at the Kasberg Prison Memorial Center:

"The first ransom was very theatrical. The bag with the money was handed over in the Berlin subway - at Friedrichstrasse. One of the ransomed political prisoners spent 17 years in prison. He later said that he couldn't believe what had happened. He couldn't believe that someone had thought of him all that time".

Dr. Jan Philipp Wolburn has written a book about how these complex negotiations - and the ransom itself - took place over decades. Our reporter met with Jan Wolburn in Kiev to understand what was behind the deals:

"It all started in 1963, just a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world was on the brink of nuclear war. So it started at a time when both sides realized that the situation could no longer develop as it had in recent years. And this prisoner exchange was an attempt to see how far we could go, if we could make agreements with the other side".

And in 1964 we were already talking about more than a hundred political prisoners being exchanged for goods. Whereas in the first deal in 1963, the political prisoners were paid in cash, in the second deal in 1964, the ransom was given in the form of goods. And that was the beginning of human trafficking, if you want to call it that. Or the beginning of ransoming political prisoners.

Both sides had an interest in keeping these deals secret. And East Germany was particularly interested. First of all, it could damage its image.

"And secondly, open information about these deals could provoke a situation where people would try to go to prison in order to be ransomed and go to the West. And there have been cases where that has happened," Dr. Wolburn says.

If you want to escape to the West, take down Vogel's cell phone number

In Spielberg's film, you could see the image of a man who played a crucial role in those negotiations. This is East German lawyer Wolfgang Vogel (played in the film by German actor Robert Koch). Vogel was involved in the negotiations to exchange Abel for Powers in the early 60s, and he would become the chief negotiator between East and West in the following decades.

"Vogel played a crucial role in the exchange processes," says Stefi Lehmann. "I attach such importance to him because it was the lawyers, not the governments, who made agreements with each other. Of course, the lawyers had to get approval from higher authorities, but ... they were the ones who negotiated with each other".

By the 1980s, many of those planning to escape to the West already knew Vogel's name, Wolburn adds:

"They knew there was such a lawyer - Vogel. And he had some contacts with the Western government to free political prisoners. And when someone tried to escape, he would say to his friends, 'Listen, if it happens that I go to prison, please tell my friends or relatives in the West. Let them activate the connections between the Western government and Vogel".

What made Vogel so special? Why was this particular lawyer trusted by both governments with such ambiguous deals? Could another lawyer have played Fogel's role?

"He looked like a diplomat. He could act, he could present himself as a spokesman on humanitarian issues. And that's something that was very much appreciated in the West. That there was someone they could talk to. Someone they could trust," says Dr. Wolburn. "He was one of those lawyers who had a foot in both worlds. He had a license that gave him access to the courts in West Germany, but he also had a license that allowed him to work in the East German system. He could go to both parts of divided Berlin. And he had the confidence of the East German government".

And he also had connections to the secret police, to the East German Ministry of State Security, and to the people who ultimately made the decisions about the ransom of political prisoners. For the same reason, Vogel is still a controversial figure in Germany.

"He is a controversial figure. But a very interesting person," says Stefi Lehmann. "On the one hand, he did a lot for political prisoners. His law firm was in constant contact with the families of political prisoners. But on the other hand, he served the party."

Vogel also distinguished himself outwardly. In the dark days of the GDR, he had a golden Mercedes, which he used to escort busloads of political prisoners to the western border. There were other lawyers who tried to take over his role. But none of them was Vogel - unable to gain the trust of either system.

"He didn't get rich off me in any way"

Vogel's last name means "bird" in German. That's why the Kasberg prison, where many political prisoners awaited ransom, was called "the bird cage." Mr. Schlosser met Vogel when he was on a business trip to Berlin:

"I decided to make good use of my time, I went to his office and asked him: I have a friend who has sent a petition to leave for the FRG. What will happen to his property, his land, his house?"

He said that if a citizen of the GDR wanted to go to the West, his property had to be sold or transferred to family members. Yes, yes, whatever the amount. It doesn't matter. He told me this and smiled as kindly as you do when you know something is wrong.

Schlosser will see Vogel again-when he's in jail, waiting for the ransom. The lawyer will tell him: "There's no need to build an airplane, you'll get to the West as it is. You'll be ransomed.

And he will confirm: yes, even then, in Berlin, he realized that there is no "friend of Mr. Schlosser who wants to go to the West. It was Schlosser himself - and he was planning his escape.

After German reunification, Vogel was accused of collaborating with the Stasi. He was also suspected of blackmailing emigrants and selling their property below market value. The Supreme Court acquitted him of all charges in 1998.

What does Mr. Schlosser have to say about this?

"I can't say anything about it, because he didn't get rich off me, not at all. He got a power of attorney from me, a document that said he was representing my interests. And nothing else. Everything else was done at the state level. I can't say that he enriched himself financially from me in any way".

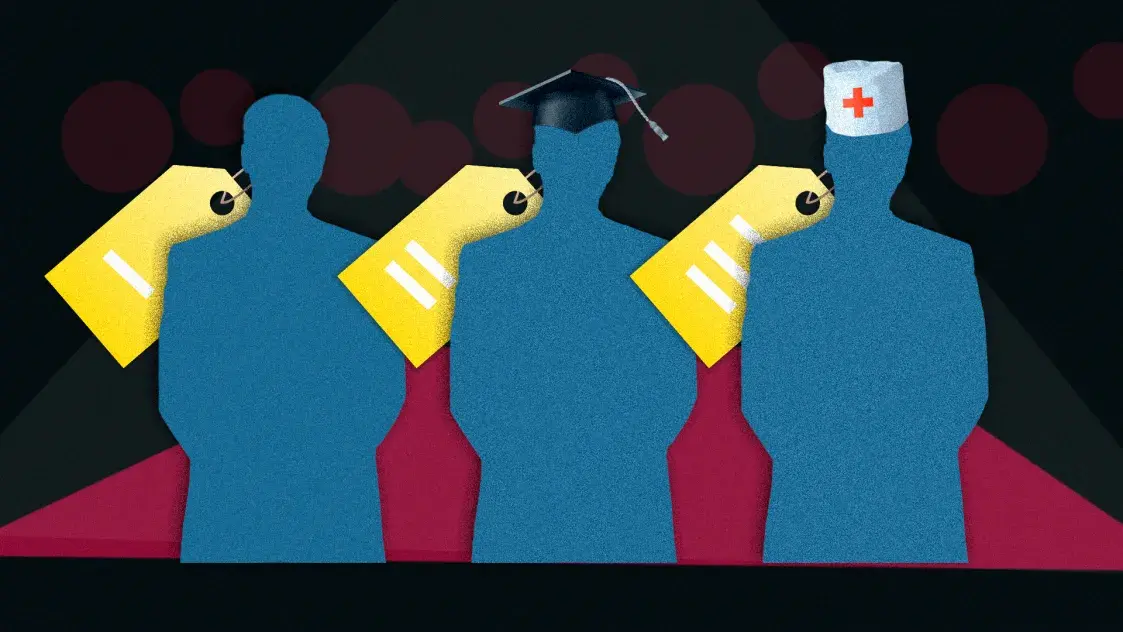

How much is a person worth? What if he's a doctor? What if he's an activist?

Historians still don't fully understand the terms of the ransom. But here's how Dr. Wolburn describes the basic scheme of these arrangements:

"There was a law firm in the West that collected names of political prisoners, and they had contacts with East Germans. They collected a lot of names of people who were in East German prisons for political reasons. This list of names was given to Vogel, and he gave it to the Stasi. They checked the list, studied who was on it and why. And then they would say, "Okay, we can sell this person, but not this one, because, let's say, he's only halfway through his sentence, and it's too early".

Eventually, these programs became a source of income for the GDR. 3.4 billion marks (about 1.738 billion euros today) came to East Germany through the FRG with the purchase of political prisoners.

"But this amount was not paid in cash," says Wolburn. "West Germany handed over goods that could be used in East German industry, for example. And in the end, the East German regime learned how to somehow resell these goods to get money for them and transfer it to a GDR bank account. And from that account they often paid their debts to West German banks. This is a very interesting circular economy.

The so-called "price of a prisoner" started at 40,000 German marks (about 20,000 euros). And by the end of the GDR's existence, 96,000 marks (about 49,000 euros) were paid for a political prisoner. Some were more expensive: for example, doctors who were needed by the GDR. Or those who "spied" for the West and allegedly harmed the East German regime".

And as all this became a source of income for the GDR, the number of prisoners increased.

"Yes, in the 1980s, political prisoners were already being imprisoned simply because, for example, people had petitioned to be released to the West. These people were arrested on flimsy pretexts," says Wolburn.

A bus with Western license plates takes ransomed people out of the GDR

Let's go back to Karl-Marx-Stadt prison. The conditions under which prisoners were held here were very different from those in other GDR prisons. The West was never supposed to get the impression that prisoners in the East were being mistreated.

Stefanie Lehmann shows us a cell:

"People who were to be ransomed could lie on the bed during the day. Witnesses from that time tell us that even the food for the ransomed was a little better than that of the ordinary prisoners".

In this prison the prisoners worked and could earn some money. But it was forbidden to take money from the East to the West. So they had to either send all their savings to their family or buy something in the local store. They could not buy much - a suitcase, for example, or some clothes.

When Mr. Schlosser came to the store, almost everything was sold out. The only thing left was a duffel bag. So he took that empty bag to the West - and sent the rest of the money to his family. He still has the bag - and the radio through which he heard the announcement from "Axel Springer".

He was supposed to fly to West Berlin and receive one million marks from Axel Springer - but he arrived in the West with an empty bag.

On the day of liberation, political prisoners were transferred from their cells to comfortable Western tourist buses. Because the deals were kept secret, the buses were secret. The license plates on them were changed at the push of a button. The bus traveled through the GDR with Eastern license plates, and when it came to the West, the plates were changed to Western ones.

"And you can imagine the emotions and feelings of people who crossed the border between the GDR and the FRG in such buses. There are political prisoners who told us that the bus was completely silent. Because when people got on the bus, they were told: "You must be silent, no one must know about the purchase, about the transfer of people, and in general about the details of this process".

And the people who got on the bus were afraid. They were afraid that at any moment they would be dragged out of there and sent back to East Germany.

And there were situations where a husband or wife would meet for the first time after years of imprisonment, and many tears were shed on these buses," says Stefanie Lehmann.

Mr. Schlosser got on the bus on wobbly legs.

"Then I sat by the window for a long time, waiting for the buses to leave. When the bus reached the border, I felt very bad, I almost threw up. And then we were at the border. I noticed that two Stasi officers had gotten off the bus during the ride. It was already about 6 p.m. It was getting dark.

What now? The bus stopped - and stood still. I thought: Why? Why is the bus stopping? But it didn't stop".

We were in a luxury air-suspended tour bus. You wouldn't even notice a pothole on the road. It's just that in the GDR there were only potholes on the roads. And in West Germany, the highway was so smooth that I thought the bus was standing still.

Then there was the first stop at a gas station, and I felt better. And I got out to get some Western air.

Schlosser opened a shop, just as he'd dreamed. And built three more planes, one of which he still flies today. When he arrives at Kasberg Prison, he calmly walks into what used to be a cell. He says he has no complicated feelings here, and sometimes takes tours.

The possibility of "selling" political prisoners was only "fed" by the GDR's temptation to intensify repression. For the West it was an act of pure humanitarianism, but for the East it was pure profit.

"You can talk for centuries about the political consequences, but you also have to look at what it meant for the people who were liberated," says Dr. Wolburn. "I don't know a single political prisoner who says they didn't want to be free. And this program was the only one on the road to peace and freedom. And if you talk to political prisoners, you'll see that these deals are acceptable to them. And this impact on human life is something that should not be forgotten and should be emphasized when it comes to ransoming political prisoners".

But can we compare these stories from the GDR with the situation in which the Belarusians found themselves? Is it possible to simply "ransom" Belarusian political prisoners from prisons? Watch the Euroradio film and join us in searching for answers to these questions.

With the support of Mediaset