Belarusian man get refugees to Azores and sends humanitarian aid to Kharkiv

"When the war is over, I'll be able to go to Europe for borshch every day" / collage by Ulad Rubanau, Euroradio

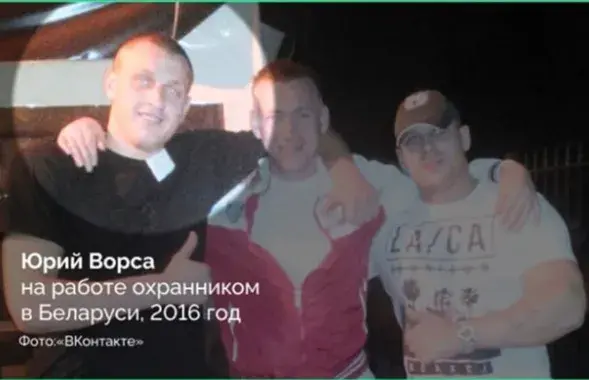

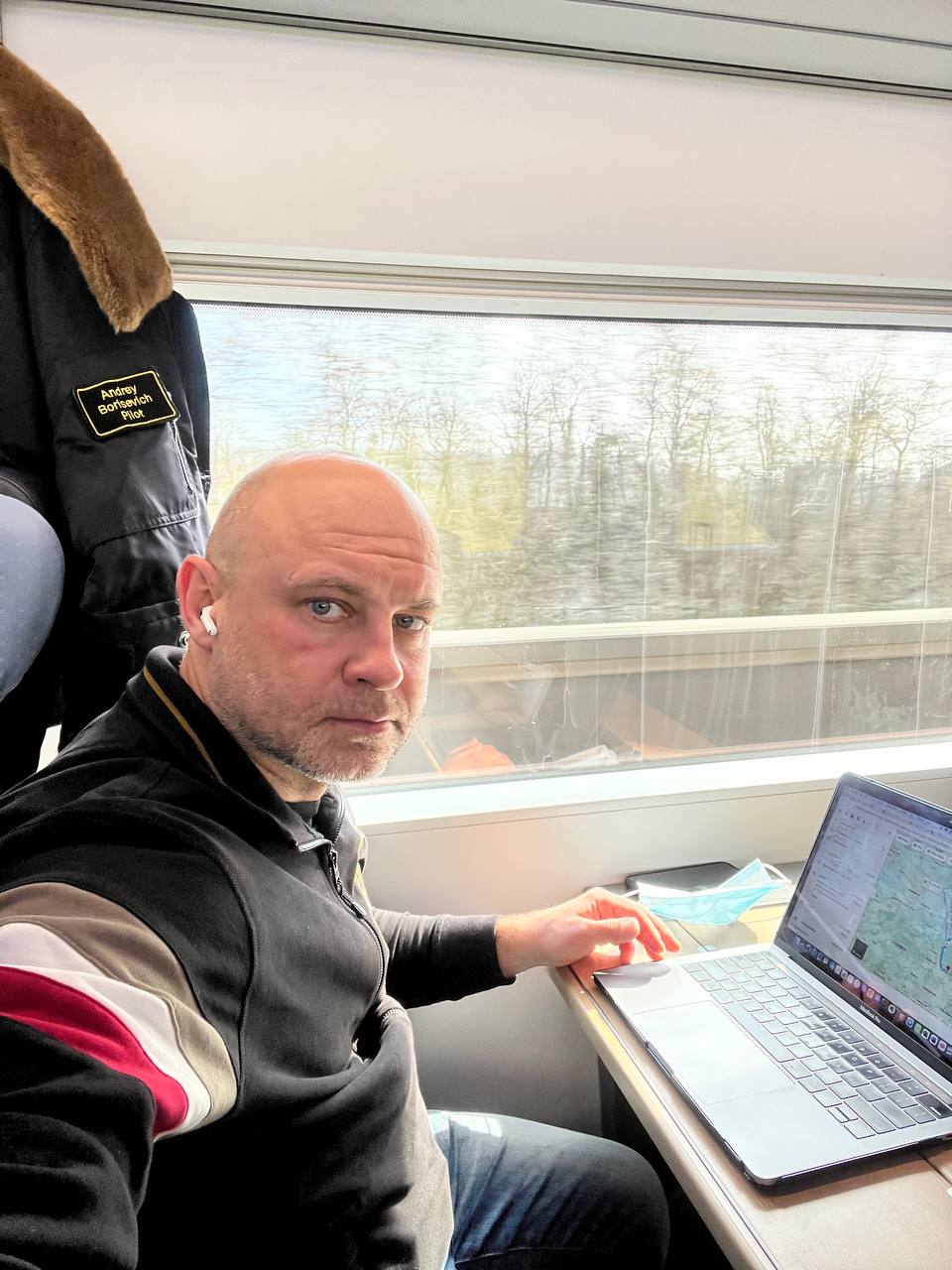

Belarusian Andrei Barysevich has been negotiating with the government of the Azores to host Ukrainian refugees and helping a volunteer warehouse in Warsaw work better than Amazon warehouses.

In peacetime, he is a businessman, owner and creator of an aviation academy in the United States. Now he should be at home in Miami, but he's in Warsaw, helping operate a humanitarian warehouse.

Read this story if you think you're tired and have no more energy.

Barysevich. "I can't fly home to Miami, nor can I rest in a villa."

Downtown Warsaw. The 'Escobar' grill bar. Inside, people smoke a hookah. Outside, at the entrance, flies a small Ukrainian flag. Bigger flags are flying all over Warsaw, but a young woman with no belongings comes in here:

"Excuse me, I was told I could get humanitarian aid here."

A waiter escorts her to the second floor.

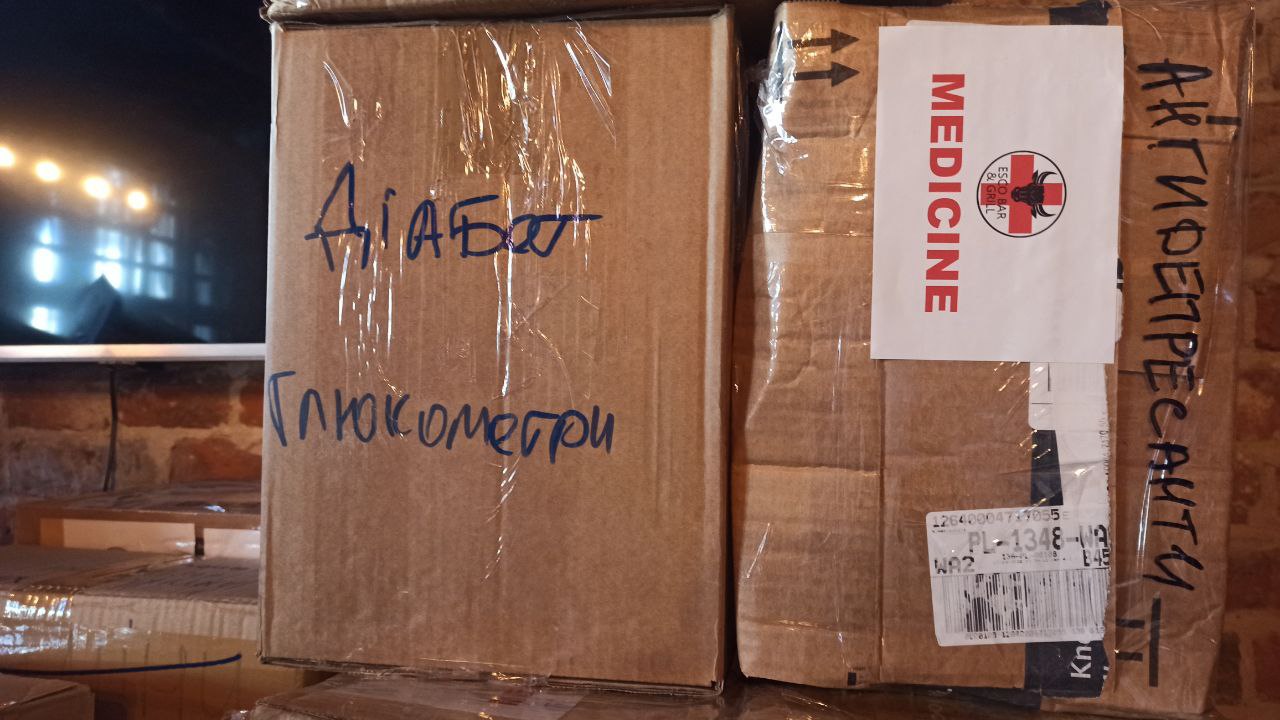

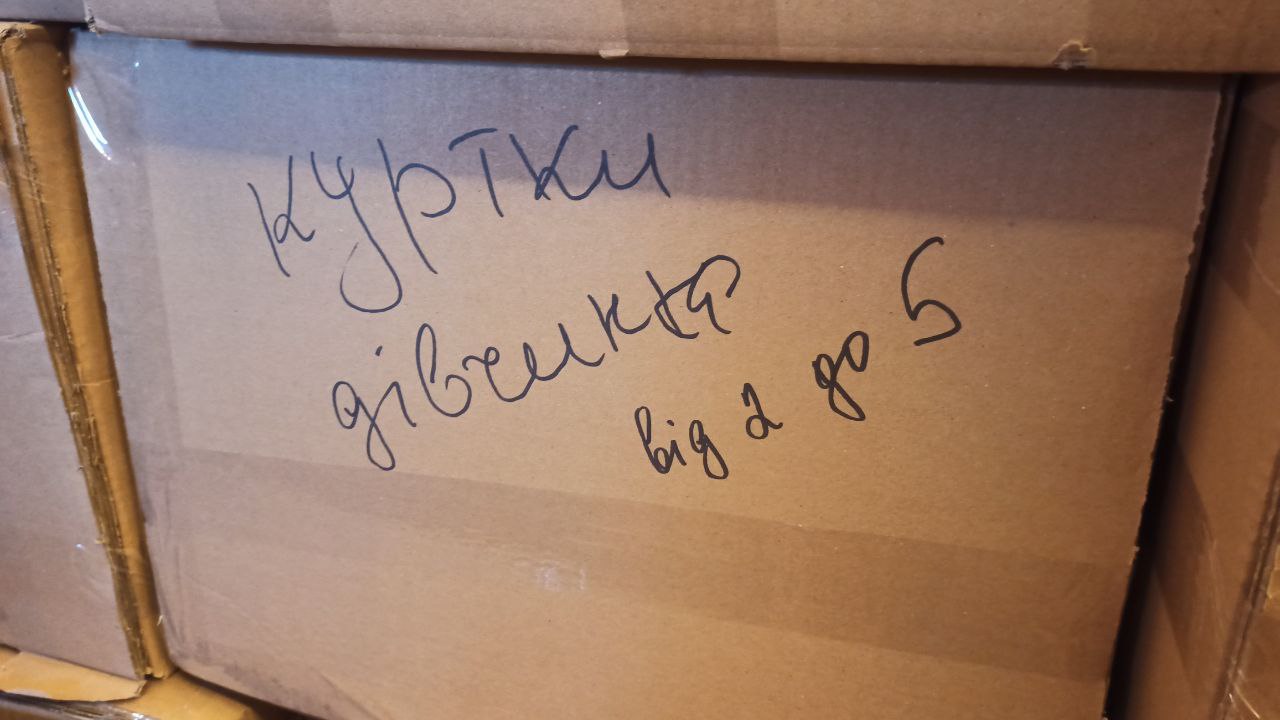

In several enclosed areas of the bar, volunteers are thoroughly packing boxes. Women's clothes, men's clothes, children's clothes, hygiene items, medical supplies, food. Separate boxes for the military.

Each box has the name of the city and the phone number of the person who will receive the package. Most of the boxes are for Kharkiv. That's where Escobar's owners are from.

In the main hall of the bar, relaxed guests smoke a hookah. At one of the tables, Belorussian Andrei Barysevich is figuring out how to send a plane for two hundred people to the Azores. But first, he will fly there himself to ensure that the government will provide refugees with a decent place to live.

"That's how we live. Non-stop for 24/7," Barysevich says.

He spent February on an expedition to Antarctica with a satellite phone and no news feed. As late as February 22, he thought he would spend March "somewhere in a villa in Spain." But as Andrei was returning from Antarctica via Sao Paulo, Brazil, the war broke out.

"I had a 20-hour layover. I read the news. I woke up. I flew to Germany the same day".

From there, my friends and I went to Amsterdam. I saw the first anti-war rally of many thousands. I saw people who were already collecting humanitarian aid. I saw the Ukrainians crying in the square. I realized that I couldn't stay away. I couldn't fly home to Miami or lay low in a villa in Spain.

Barysevich runs a YouTube channel about aviation. His subscriber, Sergey Popov, lives in Warsaw. He once wanted to study piloting at Andrei's aviation school in Miami. There was no time for flying in February, as minibuses collected refugees at the border. Sergei wrote about this on Instagram.

"I opened my Instagram stories and saw that Sergei is looking for minibuses. I called him and asked what help was needed. The answer was: we need everything. Because who was ready to evacuate millions of people on the third day of the war? No one.

So I returned to Hanover, rented a Ford Transit for nine people and drove to Warsaw. On the way, I contacted humanitarian organizations. I loaded the car up to the top in Berlin with humanitarian aid. On the way to Warsaw, Sergei explained where to unload it all. He said: come to "Escobar."

What "Escobar"? Why "Escobar"? All right.

I got there in the middle of the night. I thought I was gonna leave the car and go to bed. But as soon as I got to these doors, about twenty guys ran out and unloaded the whole car in a few minutes.

I didn't even have time to smoke, and the Ford was already empty. The guys said: "Thank you very much, you've found the right place! We have a humanitarian aid collection center here".

I said: "Very well, but give me back my suitcase, you took it along with the humanitarian aid!"

"A Portuguese man walks in: we have 22 trucks of humanitarian aid"

The next day Andrei came to "Escobar" again. He said that at that time, the owners of the establishment did not think about business at all. All the halls were filled with volunteers.

"We don't dump everything "somewhere on the border." The guys work very precisely, mostly in Kharkiv, which they know well. And so we understand that if the cargo reaches Kharkiv, our people will definitely meet it there. That is what attracts me the most.

The boxes in the humanitarian warehouse are lined up in towers from floor to ceiling. In the evenings, volunteers transfer 3-4 tons of cargo into cars in an hour. At the border, these cars will be met by a convoy, and then they will be transported to the cities through distribution warehouse systems.

Volunteers usually return here.

It was the third day of the war. I was drinking coffee. A Portuguese came in. He said: we have 22 vehicles full of humanitarian aid. We want to unload it and take people to Portugal. I say: how did you come here from Portugal? They answered: we drove for three days, in shifts, without any stops. You guys are crazy!

We unloaded their cars in an hour and a half, and now they always come to us. Whoever walks by stays here.

How are you?

Me? I stayed here as a manager and "support" guy. The "Escobar" guys handle all the logistics. Whenever there's a problem, they come to me. You need to find vehicles? We look for them. Gas money? We give you money. Need to go and buy boxes? We find a bus, a driver, go to the store to get the boxes.

Everything else that happens in the warehouse is Nadia's responsibility. Nadia is the mega brain there. Nadia comes here at noon and leaves at two in the morning.

Nadia. "We asked for help. Everyone who was lounging at our bar started helping."

Nadia is from Kharkiv. All of her close relatives stayed around the city. Someone managed to go a little farther away, where "they don't shoot much."

"We help as much as we can. It's a distraction," Nadia says.

When she talks about where the humanitarian aid comes from and sorts this aid, while she supervises the volunteers, she manages not to cry.

"When the war started, everyone here was thinking how to help. We asked for help in social feeds - and literally, in the first hour, the Poles began to come with help. People brought so much stuff: food, warm clothes, sleeping bags! We immediately started sending everything by car to Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Mariupol -- to the hottest points. Everything arrived where it was needed".

Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians help us. I do not divide anyone. And I have no complaints about the Belarusians: there are different people, just like in Ukraine. As well as in Russia. Good people come to help us. Bad people don't come to us.

These premises, which adjoin the bar, are owned by the Polish-German Friendship Society. When the war broke out, "Escobar" asked to give it up for humanitarian purposes. The Society said: sure, take it. No money is needed.

"Now we get things from everywhere: Germany, Spain, Portugal. Here, in the warehouse, we sort everything. Some things go to hospitals, others to bomb shelters or the military.

What do we send to the military? Mostly canned meat, warm clothes, uniforms. Flashlights, batteries, power banks, radios, binoculars. And a lot of medical supplies: we have a medic who sorts them out.

Nadia believed that there would be no war. Even when, just in case, all her loved ones packed emergency bags.

"She thought they'd come to an agreement. But they didn't. How did the war start for me? At four in the morning. Kharkiv was the first to be bombed. There's a border there, so it started at our place".

"Escobar" is collecting aid to send there. But if refugees come, they are not denied aid.

As we're talking, a young Ukrainian woman, Maryna (name changed) - the same one we met at the entrance to "Escobar" - comes out of the warehouse.

"Where do you come from?" Nadia asks.

"Mykolaiv."

Everyone standing nearby falls silent.

Maryna had her own recruitment agency. She helped Ukrainians find jobs in Poland. And now she keeps getting messages on her Viber with requests for help with jobs.

But now Maryna and her child live in a camp an hour and a half away from Warsaw. The child is ill. Now Maryna needs all the help she can get. She received the info about "Escobar" from her former colleagues in Warsaw.

Here, in the warehouse, Maryna found things for herself and the child. Nadia packed a whole bag of medicine for her. We managed to talk with her.

"Do you understand Ukrainian?" Maryna asks. "Sorry, I can't do it in Russian. Because we do not need to be dismissed".

Barysevich. "We need a plane and lodging for 200 people in the Azores."

Back from the warehouse to "Escobar"'s main hall. Barysevich has just handed the drivers the keys to the minibusses loaded with boxes. They will once again head across the border to Kharkiv. He is answering messages to Chernihiv: a request for help with a list of addresses and phone numbers came from there.

Then it will be necessary to control the purchase of food. This is another project of Barysevich. In 2020, diasporas helped Belarusians, fired after protests. On the third day of the war, the project was remodeled for food aid to Ukrainian cities. You can read more here.

But the biggest problem now is housing, says Barysevich.

"So I shifted my focus to finding housing in Europe and helping with transportation there. I made a deal with the Azores: they can host about 200 refugees. And they will even provide us with an airplane.

"And how did you get in touch with the government of the Azores?"

"All was done through friends. My friend Anatoly Letayev, who owns a migration agency, is developing investments in the Azores. He called me there about four months ago. I had been thinking about diversifying my business for a long time, but it didn't happen then".

And then Tolik called me: he said he flew to the Azores, arranged a meeting with the government. He was waiting for me.

The next day Barysevich was in the Azores.

"We met with the Minister of Transport. I asked for an airplane and an opportunity to bring 200 people to the Azores. The minister spoke in general terms. And then I showed him pictures. I took out my phone and started looking through the pictures I had personally taken at the border crossing near Przemysl.

The minister had tears in his eyes. "I got it. Let's talk tomorrow." When we came out of the meeting, Tolik said it would not work. And I said it would.

When this article came out, Andrei was back in the Azores. He was checking out the housing that local officials and business people had agreed to allocate for refugees.

"If an official says he has hostel beds that he is willing to give away for free, you have to ask more questions. For example, how many restrooms and showers do you have for 44 beds?"

I am familiar with the construction industry, and I know that you have to see everything with your own eyes. You have to come, open all the taps, calculate the amount of investment needed to make it all work. So I plan to spend the whole week in the Azores.

Maryna. "When the war is over, we'll go straight home."

Andrei meets Marina from Mykolaiv.

"Oh, Mykolaiv! Vitaly Kim [mayor of the Ukrainian city of Mykolaiv - Euroradio]! Do you want to go to the Azores? It's 1,500 kilometers from Portugal in the Atlantic Ocean. They are ready to host about 200 people in different conditions: from villas to hotel rooms and hostels.

"Are there any scorpions?" Maryna asked.

"There are no scorpions, but plenty of people are willing to take refugees into their homes. And during the season, there are also plenty of jobs. The minimum wage in the Azores is 750 euros. Think about it, and if you decide to relocate, write me. But the government is ready to consider only long-term relocants. Not for a month or two, but at least for six months.

"To be honest, we only stayed in Poland to wait for the war to be over. When it is, we'll go straight home," Maryna says.

"Like 80% of all Ukrainians I spoke with".

Barysevich. "When are you coming? We made eight liters of borshch."

"And this is my favorite Banderite," Andrei shows a picture of a little girl, Alesya.

Andrei drove Alesya, her mother, and her sister to Hanover the other day. From there, the family went to Paris. He often tries to solve problems remotely, but sometimes when there is a request for help, he just gets in the car and drives people to their new home.

"We became friends along the way, and we still keep in touch. An hour ago, Alesya texted me, "When are you coming? We made eight liters of borshch."

Andrei shows a message from Alesya. Alesya writes that the borshch is "the tastiest ever is."

"So when are we having borshch?"

"I think when things get better, I can travel all over Europe and eat borshch every day. And such stories are the most satisfying. I can't stop the war, but it's in my power to get specific people out of the middle of nowhere".

"How do people find you?"

"Instagrams, telegrams, chats. I have posted stories about an empty house in Hanover. Friends reposted stories. People wrote me. There is also a reputation: people know that I'll see it through if I take on something.

"How do you have the strength to keep up with such a schedule?"

"People think that I have an atomic reactor in me. There is no other secret. It's just that in my peaceful life, I didn't use up my potential to a hundred percent. You don't have to go into maximum thrust mode. It's like in airplanes: it's usually enough to fly at 60 percent power. And in an extreme situation, you add the remaining 40%".

I don't drink alcohol, and I try to sleep four to six hours a day. Do I look okay? As long as the body allows it, I can work.

"Do you have a personal connection with Ukraine?"

"Apart from a sense of global injustice? My grandmother is from near Poltava. I spent my childhood up to eight years old in the Poltava region. You can think of something that connects me to Ukraine, other than my desire to help Ukrainians".