Reportage from a refugee camp in Poland

"They don't bomb this place. And it's great to live anywhere when they don't / collage by Ulad Rubanau, Euroradio

"What is this place? Some kind of exhibition?" the Uber driver asks as he turns to the PTAK EXPO exhibition space near Warsaw.

The center's six enormous pavilions were created to hold conferences, fairs, and fashion shows. When the war began, PTAK EXPO quickly converted its facilities into a camp for Ukrainian refugees.

At its peak, 8,000 people lived here. Now it's ten times less.

"We need to go further. Yes, there, where people are smoking," we said showing the driver the way.

Some of these people have been smoking here for 11 months.

At the entrance, an elderly man goes through the papers enclosed in his passport - coupons, phone numbers, some zlotys. He is looking for the address of the company that promised to help him find a job. He is a pensioner. He can't see very well. "But you have to live somehow." A pill falls out of his hand.

"It's a sedative. A sedative," he says.

Next is the guard post. After a year of working here, the security guard now speaks some Ukrainian. Leaning on the post next to him is an 18-year-old boy who's been living in this camp for 11 months. This young man turned 17 last March, planning to become a veterinarian. At the end of February, he had to evacuate from Bucha.

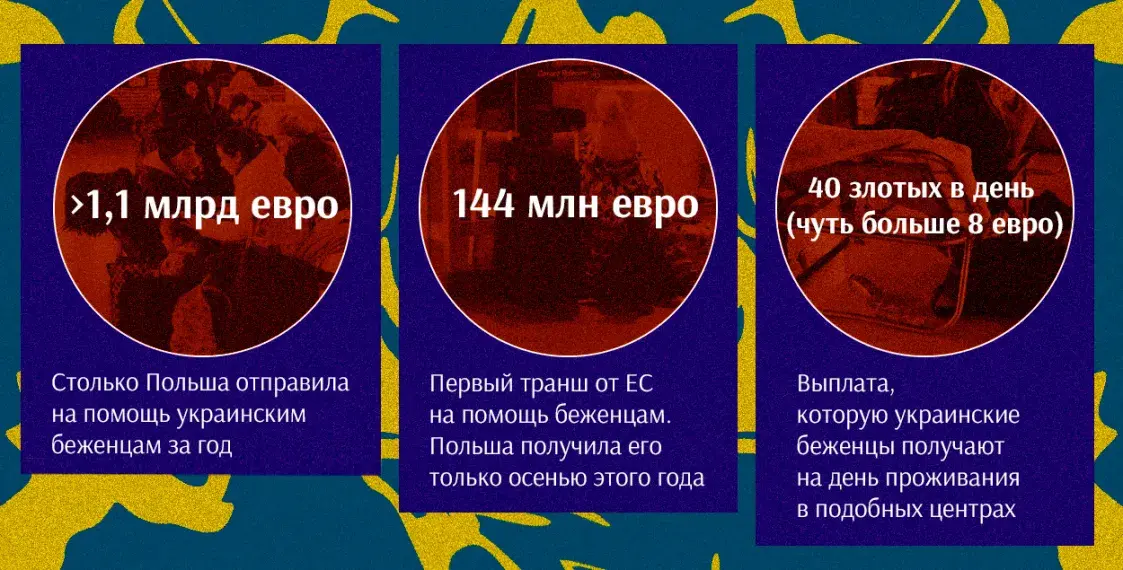

Poland has accomodated the biggest number of Ukrainians. By the fall of 2022, more than 1.2 million Ukrainian refugees were still living in Poland. And 85 thousand people were staying in such centers. All in all, there were more than three hundred such institutions in the country.

But many more Ukrainian refugees crossed the Polish-Ukrainian border. Since February 24, 2022, 9.9 million people have entered this place. Some have gone to other European countries, and more than 7.9 million have returned home to Ukraine.

"I can't wait to go home to my own people. Even under occupation"

We enter the main living quarters of the camp. The cots are a meter and a half apart. Some people use a coat rack to protect their personal space.

"What can I tell you? I have just stopped crying. I cried all morning. I cried and thought: what am I doing here?" Marina [name changed] tells us.

We do not mention Marina's real name because she will soon be going to her occupied village. Before the trip, Marina learns how to say things "correctly" so that the Russians don't suspect anything: "Right, to the liberated territory". Ahead of her, there are many checkpoints where she will have to talk "correctly".

Marina invites us in. There is a bed, hanger and nightstand. On the nightstand is a mug of tea.

"This is my bed. This is where I am stuck. I've been working for five months now, and they don't give me any accommodation. And in Poland, a bed costs 700-800 zlotys. I'm stuck. I don't know how it happened. Maybe I should have moved to a hostel after my first paycheck? I thought it wouldn't last long, so I didn't move out".

Before the war, Marina had a nice quiet life. Everyone in the family was working getting the "minimum wage". Marina was a technician at their village school.

"And on February 24 they suddenly drove in. Drove right into my mother's vegetable garden. Tanks and "Z vehicles". And people on top of these tanks.

We just stood there with my mother in shock. And so they drove through our village. They destroyed the whole road. And then the noisy grads started firing. I had never heard such noise before. I don't even know how to explain what it is - the noise of these rockets. My daughter and son-in-law were hiding in the cellars in the neighboring village, and my mother and I didn't have a cellar".

Marina's family - her husband and mother - stayed behind in the Russian occupation zone. Marina is collecting money to bring them to Poland. Ahead of her is a long journey: Poland, Latvia, Russia, the occupied territories - and finally the village where her loved ones now live. Then there will be an equally long way back.

"Can't they come to you?"

"And for what money? I'll bring the money. And they can't do it without me," Marina says. "To come, it is necessary to call, to reserve a place. Mom is over 70, and her husband has also grown old this year. They will not manage without me".

Marina's husband tells her about life under occupation. He says their village grocery store is open, everything is as it was, only there are no people there.

"So there is even work. But how can you work, when you know that every second there can be an incoming. Only pensioners are left there, and maybe heavy drinkers.

It is hard to live under occupation, because you are defenseless. With no protection. Anything may happen to you.

Soldiers came to my mother. She got scared. It turned out, they were just looking for empty houses. When they saw mom, they said, "Oh, grandma, do you live here? We thought the house was empty, we wanted to move in. Well, goodbye, then." And so they left.

People received coal. I don't know where that coal came from. It was good.

Marina says that she is afraid to go to the occupied zone. She is afraid of the shelling. But she is not afraid of Russians.

"Russians? What about the Russians? If they ask me where I was headed, I would say I was going to the liberated territory to pick up my mother".

Marina's sister has moved to Germany. She's wants Marina to come stay with her. Not asking her to come home -- her sister doesn't have a home anymore either. Just to another refugee camp.

"Basically, in the morning I got hysterical, I cried a lot, and then sat down and thought: why would I cry? I still have everything ahead of me".

"And there's no more home left"

Every day at camp there is a free breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

"There are frankrurters, sometimes sausage, cutlets, potatoes. They give you soup. Everything is very tasty. They give us as the Lord gives them. We thank them for that. We thank them for having a piece of bread. Where would I be now if not for this center?" says Sambrina. She came from the Dnepropetrovsk region. "You know how things are there now. And we still don't know what awaits us on February 24".

Sambrina has children and grandchildren at home. Sometimes they call each other, and the children tell her that the power was out four times in one day.

"They don't want to come here. They say they do not want to hide".

An announcement on the wall at the entrance in Ukrainian invites parents to take their children to the trampoline park. "Children will be treated on the spot". The adjacent wall has a request not to have parties and not to bring alcohol.

Everyone who moves in or out of the camp checks in at the front desk so the administration knows how many people are living here right now. There are now 850 people. Pillows, blankets, hygiene products for starters -- everything is free for them.

"I am from the Kherson region. I have been living here since May. Living and working. And I went away for a month," says Rida.

"What about your home?"

"There is no home any more. My house was on the liberated side of the Dnieper. But there is nothing left intact in my village".

Here you learn to live anew, it's not how we lived at home. They live differently here, and you have to get used to the way they live here.

"Here in the camp?"

"Here in Poland. Sometimes you think that some things are better in Ukraine. But maybe it's better because it's yours, it belongs to you. You perceive it in a different way," says Rida.

"And what language do people speak here?"

"I get by with Surzhyk. There are no problems here because of the language. It's the reason the war started.

A school for children opened here in September. The teachers who work there are also refugees from Ukraine. At the school, children are taught Polish, among other things.

"There is nothing to tell. Nothing good anyway"

They show us a place where we can recharge our gear, a laundry, a medical center, and a separate room where we can get free pet food. People hardly pay any attention to the journalists or to each other. Some people are reading, others are browsing photos on their phone.

"We got these from the guys at the front. This old man is already gone. Yes, the grandfather is gone".

There are a lot of beds, a lot of people, a lot of people with children, a lot of pets. Still it's quiet here. It's quiet even in the smoking room. People are reluctant to tell their stories.

"I didn't want to leave for a long time. I thought: where can I go at this age?"

"And how old are you?"

"Sixty-three. I work at Zabka and I understand that it is very hard for me to work the way the young guys work.

I have been here two weeks. I left Kherson. Excuse me, I'm not a very talkative person. And there is nothing to tell. Nothing good anyway.

On the first day of the war, I went to the store, and there was a huge line for groceries. People said it was war. I couldn't believe it.

Then the occupation. I hardly saw any Russians. Well, I did see them -- there were thirty people at our checkpoint. The commander was a somewhat reasonable man. He said: don't touch us, we won't touch you.

I spoke with the Donetsk guys four times. Why? They went for lunch in an open car. One of them spoke Ukrainian. We got talking. He told me: We destroyed Mariupol. I'll take you there, I'll show you.

I told him: At least the Russians are paid posthumous money, but they don't even consider you a Russian, you're nothing to them. He said to me: how can I be nobody? I have a Russian passport. I am an idea-driven man. The conversation ended like this: I'm going to hit you on the head with a buttstock.

"My friends advised me to go away for work and help my daughter"

"I loved walking along our embankment in Dnipro. It is one of the most beautiful embankments in Europe".

Yevgeniya had not been in Dnipro for 11 months. She left on March 12, when drones started flying over the city.

"It was very scary. I was scared to leave, and scared to stay. But her friends friends advised me to go away for work and help my daughter. And so I left.

Poland received me well. I didn't have much money at first, so I didn't rent a place, I lived in centers like this. At first, I lived in this center for a month. Then I lived in another center, also in Warsaw. Then I moved to Węgrów. They offered me a job and accommodation for three months. I took it. I worked in a hotel and in a carpentry shop. Three months ended and I had to come back here. Now I am looking for a job again, with accommodation.

There are jobs in Poland. There is a lot of work for those who want to work.

Yevgeniya worked, sent money to her daughter, and by August she too was able to leave Ukraine.

"She has a baby on her hands, she couldn't live in such a camp. So she went to Bulgaria. She lives and works there now. Maybe I will join her too.

Yevgeniya's daughter is a bandura player. Bandura is a Ukrainian folk musical instrument.

"We had a Dnepropetrovsk ensemble "Cherevnitsy", and my daughter traveled all over Ukraine with it. So she is a carrier of Ukrainian folklore. She opened the world of music for me.

When it gets sad, Yevgeniya turns on Ukrainian music on her smartphone.

"Talk about anything but the war"

At the beginning of the war there were many volunteer psychologists working in the camp, but back then people were not ready to talk to them. Now, to get to a psychologist, you have to sign up for a waiting list.

People in the camp hardly ever talk about the war. Not just with journalists.

"Some complain about the food at the center, others complain about their neighbors. People are ready to talk about any problems - as long as they don't recall what happened to them in Ukraine," psychologist Tatiana tells us. She is from Luhansk region, she left Ukraine in early March and has been working as a psychologist at the center for a year now.

"So who is complaining here?"

Several of the center's residents, three young women, immediately defended the center. They came to the camp at the very beginning of the war. At first they just lived here, then they started volunteering. Now they work and live here.

"You know, only those who come from Western Ukraine are horrified by these living conditions. And those who survived the bombing with their child, sitting in the basement, are glad when they get here. They don't bomb this place. And it's great to live anywhere when they don't," says Anna. She comes from Izyum.

"Lavish conditions means it is warm, there is running water, when there are free detergents. And nothing flies over you. No one was willing to help us for so long. But they do now.

The camp was ready for thousands of people to come here in winter. In Warsaw, they were sure that the winter and the cold would provoke a new flow of refugees from Ukraine. But that did not happen. The cots and blankets prepared in reserve were left unclaimed.

***

It is 10 kilometers from the camp to Warsaw.

"Do I often go to Warsaw? You know, on weekdays I mostly work. On weekends I try to be at home.

"At home means here, in the camp?"

"So it is, yes. We didn't even notice when we started calling it home. But I want so much to go to my real home.

Or at least walk in my home streets.

Produced with the support of Mediaset